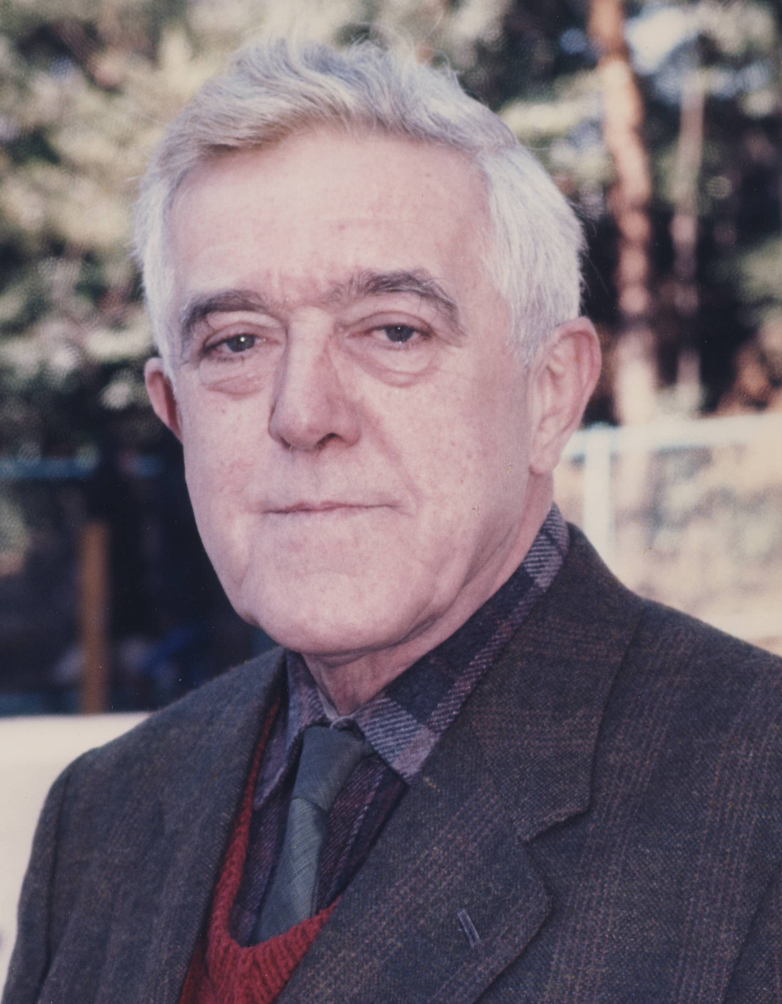

Jan Van Bragt (1928–2007)

Early on the morning of Easter Thursday, 12 April 2007, Jan Van Bragt passed away quietly at the age of seventy-eight. During the year previous his health had begun to deteriorate until in the final days of 2006 he was obliged to leave Kyoto and take up residence with his religious congregation in Himeji. On 21 February he was hospitalized with lung cancer and was operated on some weeks later. After a brief period in a semi-comatose state, he regained consciousness but was never to speak again.

Jan was born in the city of Sint-Antonius-Brecht in Flemish Belgium and entered the Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, the national missionary order of Belgium, at age eighteen. Six years later, in 1952, he was ordained a priest. After receiving his Master’s degree in philosophy he entered the doctoral program and at the same time lectured at the Congregation’s seminary. Five years later he received his doctoral degree in philosophy from the University of Leuven with a thesis on Hegel and immediately set sail for Japan, landing in December of 1961. He undertook eighteen rigorous months of training in the language and then spent another eighteen months working as an assistant pastor at the Sakai Catholic Church near Osaka. In spring of 1965 he was accepted as a research student at Kyoto University, where he spent the next six years studying with Takeuchi Yoshinori and Nishitani Keiji. In 1971 he was named provincial superior of the Congregation in Japan, a post he held for five years until it was interrupted unexpectedly by the request to serve as the first acting director of the newly established Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture.

For the next fifteen years he brought the fledgling Institute to maturity, galvanizing the young and inexperienced staff into a community of scholars devoted to exploring the largely unknown and uncharted waters of interreligious dialogue in Japan. Among his first projects was the inter-monastic exchange that brought leading Buddhist monks and nuns from Japan to European monasteries and vice-versa. At a concluding symposium in Japan he served as chair juggling Japanese, Flemish, German, French, and English with the skill and poise for which we all remember him. After a flurry of publications on the project, he left the project to others to carry on—as it has to this day, having reached a second generation most of whom no longer know the inaugural role that he played.

Jan was also a key figure in the Japan Society for Buddhist-Christian Studies, founded in 1982. In addition to bringing the central office of the Society to the Nanzan Institute, he served as president from 1989 to 1997. During his years at the Nanzan Institute he was in demand around Japan as a lecturer or partner in dialogue. For many years he traveled around the world in the same capacity and was invited for longer periods to teach in Canada, Belgium, the United States, and the Philippines. From 1985 to 1990 he served as a member of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue. In his thinking and writing, his study and reading, as well as in his moral concerns, Jan straddled any number of civilizations, histories, literatures, and cultures. In the end, however, it was in Japan that he felt most at home, where he found a loom on which to weave the things of life into a single view of the world.

At his funeral Jan Swyngedouw, a fellow Flemish missionary and long-time colleague at the Nanzan Institute, delivered a thoughtful and touching tribute to a man who had always shied away from honors and recognition, preferring to let others stand on his shoulders and even accept the credit that was rightly his. He told of going through Jan’s library (the philosophical portion of which he graciously donated to the Centro Studi Asiatico in Osaka) and being struck by the number of volumes on mysticism. Like all of us, he knew of Jan’s academic interest in the Christian mystics as a bridge between religion, but as he read through comments in the margins he came to realize what most of us had never noticed: how deeply Jan’s own spirituality was rooted in the mystical tradition, where he found a way to ground his ideals as priest, educator, and scholar. The simple life he led and the simple tastes he cultivated were his way of resisting the relentless pressures of the age to acquire more and consume more. They were also a sign of his deep belief that the important inspirations of one’s life—like the inspiration to dialogue among religions—need to be let blow where they will and protected from attempts at institutionalization and expropriation by specialists.

I lived with Jan for eighteen years in Paulus Heim, a small home we had made to house a community of scholars and to give lodgings to hundreds of men and women from around the world who came to spend time at the Nanzan Institute. Of the many memories that crowd in on me as I look at his photograph sitting on my desk, most of them have to do with discussions we had at home. How many late nights we spent sitting in our living room discussing religions and philosophies East and West with visitors from abroad like Fritz Buri, Hans Küng, Raymund Panikkar, Frederick Copleston, Ivan Illich, Ernesto Cardenal, Jan Sobrino, Gustavo Gutiérrez, Bryan Wilson, Heinrich Rombach, William Theodore deBary, Julia Ching, Sulak Sivaraksa, and Frederick Franck—not to mention the almost endless stream of scholars from within Japan! Whether the visitor was a young graduate student or a world-renowned scholar, Jan had a way of making everyone feel comfortable so that the center of conversation could move gracefully from one person to the next. I have always said that to me he was the soul of dialogue, and I mean that as literally I know how to use the word “soul.” Quietly, undramatically, often with good humor but just as often without any visible sign of his own presence, he had a way of keeping a discussion breathing in and out.

Two memories stand out above all others as typifying the kind of man he was. The day I arrived in Japan I headed straight for the Institute, which I had not seen except in architect’s sketches. Jan had been alerted to my coming and stood there waiting for me at the front entrance. He reached out his hand, introduced himself, and welcomed me. As I pulled away after a polite handshake, he reached out and took hold of me with his other hand. “Two trunks of books have arrived, Jim, and we put them in your office. Please take what you need from them and have a good look around the building. We are only a few people and most of the rooms are still unoccupied, but do have a good look around. It will be the last time you pass through these doors until you can read and write and discuss freely in Japanese. Until then, we can get along better without you.” And then he smiled and led me in. At the time I remember finding his words strange—warm, but strange.

It was only when I had completed the task he had set me and returned to the Institute that I realized how generous his gesture had been. Beginning a new Institute without any experience, the skeletal staff was overworked and disoriented, with nothing to guide them but the vague ideal of creating an oasis for people from different religions to talk to one another on a scholarly level. The amount of work that had to be done to organize an office, compile a library, arrange for scholarships, consult with religious and academic leaders, and the like was immense. And yet there he was, telling me that the only thing I had to worry about was getting as good a preparation as I could get. No schedules, no deadlines, no pressure. This was only the first of many occasions that he took to insure that organizational concerns would always come second to making the Institute a center of excellence able to adjust to the needs of its members. Whatever our personal failings over the years to live up to the ideals, Jan was always there to remind us when we forgot, to catch us when we fell, to get us back on track when we were distracted. Even granting the liberties one can take in an In memoriam, this may sound like a lot to say of one man. The fact is, I know of no other person in my life of whom I could say the lot and know it to be true. For as long as he was here and each time he would return, there was never any doubt: Jan was body and soul everything that has been best about the Nanzan Institute.

I also remember the intense experience of having Jan as my teacher. When he had completed his translation of Nishitani Keiji’s master work, Religion and Nothingness, after sixteen years of consultation with colleagues and countless hours of discussion with Nishitani himself, Jan felt that the manuscript needed one more thing: the touch of a native English hand. I was flattered when he asked for my help and set about as best I could to remove some of the rough edges and bring a certain flow to the prose. I would work during the day, the Japanese text open before me, to produce a few pages of what I thought were flawless work. Then at night, after we had cleared the supper table and watched the evening news, he would sit down with me and go through my work word by word, unravelling one thread after another of what I had woven so carefully. In the course of many months, I learned more about the scholarly conscience of reliable translation work than I would have imagined possible. There were no computers to lighten the load; I would have to type and retype the pages over and over until he was satisfied that I had gotten it right. Every few hours he would become all excited over the smallest turn of phrase that I had gotten right. For the rest, he was all doubts and questions. When it was done, I never had the slightest thought that it was my work. But neither did I feel that he had taken advantage of me. It was a teacher’s gift that in satisfying the demands he made on himself he taught me to demand more of myself than any teacher I have had before or since.

When Jan retired from Nanzan University, he spent two more years at the Institute as a professor emeritus and then moved to a small room on the north end of Kyoto where he lived until the final months of his life. From the time of his years at Kyoto University, the city had a special place in his heart. When there would be a lull at the Institute, or when he was facing a deadline for an essay and needed to get away from everything, he would often announce at supper, “I am going to disappear tonight for a few days.” We all knew this meant he was heading for Kyoto and would return in two or three days with a smile on his face and a completed manuscript in his briefcase.

Even after retiring to Kyoto he would visit us every couple of months to catch up on periodical literature and renew contacts. These were visits we looked forward to as much as I know he did. Beginning in 2006 we began to discuss with him the possibility of having him return for a year to inaugurate a new Chair for Interreligious Research that we were establishing at the Nanzan Institute. The offer coincided with a rapid decline in his health, and in the end he told me, choking back the tears, that he did not think he would have the strength to take the position on.

His academic contributions and the development of his own thought are matters that require more attention than this short memorial can give them. I am preparing a special lecture for the 2007 annual meeting of the Japan Society for Buddhist-Christian Studies where I hope to go into further detail and prepare a list of his major publications. For now, I can only write the words I hoped I would never have to: Farewell, Jan. You have been a good teacher and a better friend. Our world is a size smaller without you.

James W. Heisig

James W. Heisig